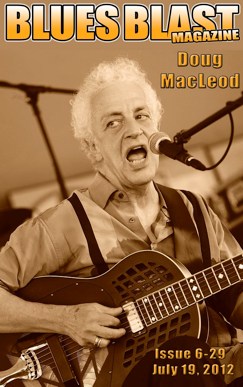

BLUES BLAST Interviews Doug at The Mississippi Valley Blues Festival

“I had heard all the stories about her and I was real nervous. So I just played real simple, tasteful guitar – Albert King style – with not a lot of notes but with a lot of feeling,” MacLeod said. “So we get done with the set and I'm sitting by myself – I thought I had done alright. Big Mama comes over and got right up in my face and said, 'You like me?' I said, “Yes, Mama, I like you.' She said, 'What you like about me?' And the first thing that came to my mind and out of my mouth was, 'I like your eyes.' I was sweating, but she said, 'Ohhh, baby.' And she turned to George Smith and said, “George, you know what little Doug said to Mama?' And you could tell George was worried about me and he just shook his head. Then Mama said to him, 'Little Doug likes Mama's eyes.' And George went, 'He do?' But from then on, Big Mama loved me. I could do no wrong with her.”

Over the ensuing years since that fateful evening when he adroitly managed to woo Big Mama Thornton, MacLeod has really earned his stripes in the blues world and has became a living, breathing example of how the forefathers of the genre used to carry out their business, armed with not much more than just an acoustic guitar and a sack full of hand-crafted tunes, traveling the world by any available means.

There's not many fans of the blues that have not had some form of contact with MacLeod, either by listening to one of his 20 albums, by reading the charming and amusing stories he wrote for Blues Revue magazine for a decade, or by gazing at his portrait that hangs inside the Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale, Mississippi.

MacLeod's latest studio effort, Brand New Eyes (Reference Recordings/Fresh), garnered him a pair of Blues Music Award nominations this year, one for Acoustic Artist of the Year and one for Best Acoustic Album. His name is regularly found when the BMA nominations are handed out, but winning has proved a bit elusive to MacLeod, although he doesn't seem to be too down in the dumps about wearing the 'forever a bridesmaid' tag. “Well, yes and no. I've done an awful lot of records and have had a real good career, so on that side, it doesn't affect my career much,” he said. “But on a personal note, I'd love to win one. You know what I mean? For me to sit and say to you that it doesn't bother me … that's not true. I'd love to win one. I'm starting to feel like Susan Lucci, you know what I mean? Always nominated and never winning one.”

MacLeod first got his feet wet in the coffee house folk scene back in the 1960s, an extremely fertile time for music and a period that not only saw the birth and rise of future superstars like Bob Dylan, but also saw the 're-discovery' of forgotten legends such as Skip James. And according to MacLeod, the differences between the folkies and the blues cats was really paper-thin. “Well, I realized that the blues are a great medium for singer-songwriters. And that's what I am – a singer-songwriter. But the blues is the thing I do. When you think about it, Son House was a singer-songwriter. Blind Boy Fuller was a singer-songwriter. Big Bill Broonzy, Lightnin' Hopkins, Robert Johnson, those guys were all singer-songwriters. They were folk musicians. And I just like to think I'm kind of carrying on that tradition.”

While they may have shared several similarities, there may have also existed a bit of envy between the folk singers and the bluesmen of the day during that time frame.

“Back in the late 60s, when this folk movement was going on, the blues guys were kind of like the rebels of that movement,” said MacLeod. “The folkies were jealous of us blues guys because of our lifestyle and the way the girls were all after us.” When all the layers are peeled back from a good song, what you have at its very core is a story. That's no doubt one of the reasons that MacLeod has became such a prolific and gifted songwriter lies in his ability to tell a good story. MacLeod's stories and songs have found a way to get to the very essence of the human condition – both the good side and bad side. That ability was quickly recognized by many throughout the industry, including by the one man that most point to as the greatest blues songwriter of all time.

“I was fortunate enough to meet Willie Dixon when he was in L.A. And he actually liked a song of mine. That's how we met. We were at a benefit for Shakey Jake Harris and I was sitting right next to him, as close as could be, and was really nervous. It would be like a baseball player sitting next to Henry Aaron,” MacLeod said. “And he said to me, 'I love that song you wrote called “Grease in My Gravy”. And that's one of my funny ones, right? So that broke the ice and we started talking and he told me the blues is the true facts of life. Everything that goes into life.” That conversation with Willie Dixon about the DNA of a blues tune took MacLeod all the way back to the 1960s and a gentleman by the name of Ernest Banks who lived in a small Virginia town, as did MacLeod at that time.

“It was a small town back then. Now it's not, it's a big, ole place, but back then, in order to find someone's house, you had to know which Magnolia tree to turn by and then you'd go down a little path about the size of two tire tracks and then you were there,” he said. “And I was singing all these songs at that time about picking cotton and all this stuff. And this man told me, 'Never write or sing about what you don't know about. If you ain't lived it, you got no business singing it.' And I said to him, 'Well, Mr. Banks, I don't know … what am I going to write about?' And he looked at me with that one eye he had and said, 'Have you ever been lonely? Have you ever needed a woman or some money for that little room where you stay down there?' And I said, 'Sure.' And he said, 'That's the blues, too. Write about that.' I thank my lucky stars that I was fortunate enough to have met Mr. Ernest Banks back when I did.”

© All rights reserved for Doug MacLeod • Design and hosting powered by www.studiomdesign.ca

Armed with that powerful advice from a man that surely knew what he was talking about, MacLeod started authoring a string of songs that rapidly weaved their way into the very fabric that holds the blues culture together. A number of MacLeod's countless compositions have been covered by artists like Joe Louis Walker, Coco Montoya, Billy Lee Riley, Albert King, Dave Alvin and many more. “I remember the first time I heard Albert Collins do a song of mine, “Cash Talkin' (aka The Workingman's Blues). And one of my favorite organ players – and Albert's, too – was Jimmy McGriff. And he played organ on that song. One of my songs,” MacLeod said. “And with Albert playing and singing on it... man I nearly died when I heard that.” The late, great Eva Cassidy, an immensely talented singer who unfortunately never really achieved stardom until after her death, also chose one of MacLeod's songs to cover.

“The first time I heard her version of “Nightbird” was when my wife and I were on our way back from National Guitars. I'm a big St. Louis Cardinals fan and they were playing the Dodgers and Vin Scully was going to be on the radio announcing it. And I was going to be in baseball heaven. My team with Vin Scully on the call,” said MacLeod. “We were in the car and the game was about to start, but my wife Patti said there was something she wanted me to hear. I said, 'Patti, it's the Cardinals and the Dodgers … Vin Scully.' She said, 'Douglas, there's something you've got to hear. ' So she puts in this CD and I heard it (“Nightbird”) and said, 'That's my song.' And her version moved me so much that I had to pull over to the side of the road and listen to it. And I'll tell you the truth without being too maudlin – a little tear came out of the corner of my eye. And I have yet to do that song again. I tell people that is the version of that song to listen to. She did such a great job.” MacLeod spent the first part of his life in Raleigh before his family re-located to New York, where he was soon turned on to the wonderful sounds of doo-woop and R&B classics of the day.

“They had these big, ole R&B shows at the Brooklyn Theater, but guys like Big Joe Turner were on there, too. So I listened to that kind of music in New York,,” MacLeod said. After moving once again, this time to the Midwest and St. Louis, MacLeod was exposed to the blues. “Well, it was the blues, but it was still called R&B in those days,” he said. “But it was Albert King, Lightnin' Hopkins, Little Milton and all the soul guys. And there were two stations, one on the left (side of the dial) and one on the right and they played that kind of music 24 hours a day. And that's when I started to want to be around that kind of music.”

Before long, MacLeod decided to enter into the fray himself, with the bass guitar serving as his first portal into the world of playing live music. But, it wasn't long before MacLeod realized the bass guitar might not be the proper instrument for him.

“I couldn't get any girls. I couldn't get any girls with the bass, so I switched to the guitar,” he laughed. “So I started playing acoustic guitar and when I joined the Navy, I started playing in the coffee houses and so on.” His dalliance with the acoustic guitar took a bit of a left turn when MacLeod fell under the powerful pull of Kenny Burrell and B.B. King's jazzy, electric guitar playing.

“I heard those guys and couldn't get them out of my head. So, I changed over to the electric guitar,” he said. “And my first four albums were with an electric band. But then I realized that I really wasn't connecting with people – because I'm a storyteller, too. So I told my wife that I wanted to dissolve the band and go back to being a solo act. I knew it meant playing smaller rooms and a little less money, but I thought I would be happier and be able to touch more people that way. And without blinking an eye, she said, 'Do it.' And that turned out to be a great decision she made. That was in '92, so 17 albums later, she made the right decision for me.”

And MacLeod seems truly happy traveling the world by himself, without band mates, a wall of amps or a huge entourage.

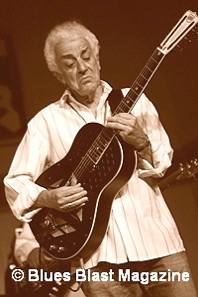

“I'm comfortable with all that. Me, I travel with one suitcase and one guitar, that's it,” he said. “That's what the real old cats used to do. Me and Honeyboy (Edwards) used to talk and you know, back in his day, they didn't have two or three guitars. They just took one with them and they were lucky to even have that one. They tuned it to the different tunings and that's what they used. I have one National now – one that I call Moon – it's a black M1 and it's one they made for me. I love it. They called and wanted me to have one that was in the catalog, so they made that one for me. And I use it for everything.”

Everything from playing small blues tents in the American heartland to some of the world's biggest stages at the world's biggest festivals overseas. “That doesn't bother me at all. I've played some big, big festivals in Europe and the people will ask me, 'Are you alright on that stage all by yourself?' And I absolutely am. I love it. I'm just real comfortable as a solo act.” As anyone who has ever read an installment of Doug's Back Porch in Blues Revue knows, George “Harmonica” Smith and Pee Wee Crayton were a couple of central – and colorful – characters in the development of MacLeod's life. On and off the band-stand. And it's clear that he very much treasures the time he spent, and the lessons he learned, from Smith and Crayton.

“Their smiles. I miss their smiles. I think back about the friendship and the camaraderie that we had. And just what a joy it was to be with them,” MacLeod said. “The laughter and the lessons in life … I mean, George was a very spiritual guy. A lot of guys knew him before, when he was a rascal, but I knew him as this wonderful, spiritual gentleman. And I was easily accepted by them - Pee Wee's the Godfather of my son.” All it takes is just a casual glance over some of MacLeod's columns to understand that he not only has a way with putting together words that rhyme and setting them to life with music, but that he is also a highly-entertaining author of prose on a page, as well. In addition to his journalistic efforts and his singing, songwriting and guitar playing, plus, the appearances that he does in various workshops and the occasional instructional DVD that he puts out, MacLeod never seems to hit the idle switch for very long. But no matter what he's doing, you can bet that the blues are involved and that there's another song, just around the corner.

“Blues is what I call a deceptively simple music. It tells a story and if you listen to that story, it can change your life,” he said. “There's a song on my last album (Brand New Eyes) called “Some Old Blues Song” and I wrote that song about the power of how one blues song can reach into your heart and your soul and somehow make it to your brain and tells you that you can make it. It gives you confidence and reassurance.”

And there's nothing like a shot of confidence and reassurance when a case of the low-down, in-the-gutter blues rears its head. “In my mind, this is not a music about suffering. It's not a music about partying all the time. It's a music about overcoming,” MacLeod said. “Not everybody gets a good shake in this world. Most of us don't. And this music talks about how you overcome that. When you're in the bad times – know that you can overcome. And then when those bad times are gone, this music helps you celebrate that, too.”

Visit Doug's website at www.doug-macleod.com.

Photos by Bob Kieser © 2012 Blues Blast Magazine

Interviewer Terry Mullins is a journalist and former record store owner whose personal taste in music is the sonic equivalent of Attention Deficit Disorder. Works by the Bee Gees, Captain Beefheart, Black Sabbath, Earth, Wind & Fire and Willie Nelson share equal space with Muddy Waters, The Staples Singers and R.L. Burnside in his compact disc collection. He's also been known to spend time hanging out on the street corners of Clarksdale, Miss., eating copious amounts of barbecued delicacies while listening to the wonderful sounds of the blues.

Featured Blues Interview - Doug MacLeod

Go back to » www.doug-macleod.com

Archives Doug MacLeod Blues News